British taste buds might not be so happy today without the innovation and entrepreneurialism of one Carlo Gatti. He is, after all, credited with being the first to offer ice cream at an affordable rate to the general public. He rose from a poor, isolated region in the Blenio Alpine Valley to become one of the most brilliant business marketing gurus of the Victorian era.

Gatti was born in 1817 in Canton Ticino, a predominantly Italian-speaking region in Switzerland. Common speculation puts his place of birth in the village of Marogno which was then within the boundaries of the commune of Dongio. He was the youngest of six siblings born to Stefano and Apollonia Gatti.

As a child, Gatti showed little ambition, and regularly played truant from school. Like many young men in the region, Gatti couldn’t wait to leave in search of greater opportunities throughout industrialized Europe. A harsh beating at school provided the final push Gatti needed, and rather than returning home, he simply set off on a 600 mile walk to Paris, where his father was running a small business selling chestnuts.

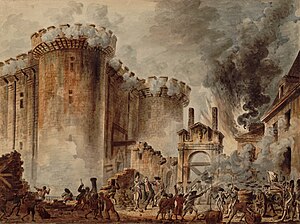

Paris at the time was a hub of innovation and business. Cafes throughout the city offered coffee, ice cream and live music to all classes of people, and young Gatti certainly must have absorbed the atmosphere and learned from their management and business strategies. Rather than settling into the family business, however, Gatti turned his eyes on greener pastures.

In 1847, at the age of 30, Gatti arrive at Dover with his young wife, Maria Marioni. He quickly found a home in London and settled into life in the bustling Italian community in Holburn. He started out with a business he knew well, selling chestnuts and waffles from a little stall. Before long, however, two of his children died, and some suggest that this event spurred Gatti to greater ambition in pursuit of a better life for his family.

By 1849, Gatti went into business with Swiss chocolatier Battista Bolla. Together they opened a café restaurant, specializing in chocolate and ice cream – a treat previously reserved only for the very wealthy. The duo set up a Parisian chocolate making machine in their front window to attract passers-by, and soon business was bustling.

After exhibiting his chocolate machine at the Great Exhibition in 1851, he opened the first of five shops in Hungerford Market that thrived on selling the original “penny licks” – a penny’s worth of ice cream served in a shell. His penny ice cream was such a novelty that London’s streets were soon bustling with Italian ice cream vendors – or “Hokey Pokey men” – tempting customers to “ecco un poco” or “taste a little”.

After exhibiting his chocolate machine at the Great Exhibition in 1851, he opened the first of five shops in Hungerford Market that thrived on selling the original “penny licks” – a penny’s worth of ice cream served in a shell. His penny ice cream was such a novelty that London’s streets were soon bustling with Italian ice cream vendors – or “Hokey Pokey men” – tempting customers to “ecco un poco” or “taste a little”.

In 1854, Hungerford Hall burned down, damaging the adjoining market. Fortunately, Gatti was insured and he was able to use the compensation to replace the structure with a grand music hall. Just a few years later, he sold his music hall at a healthy profit to the South Eastern Railway, and the hall was turned into Charing Cross station.

With the proceeds, he set up a second music hall which later became a cinema. Around the same time, Gatti built a huge “ice well” where he could store the tons of ice that he began importing from Norway. In 1862, he built a second ice house, and was established as the largest ice importer in London. Capitalizing on this, he set up a fleet of delivery carts to supply ice for household ice boxes.

Due to his entrepreneurial spirit, and careful business strategies, Gatti went on to found new confectioner’s shops, cafes, restaurants, and even the world’s largest billiards room. When Gatti died on September 6th, 1878 in his home town of Dongio, all of his London businesses closed to pay their respects to the life of this immigrant who had truly achieved greatness.